The debate about the state of the American health care system has been heating up lately. A series of articles in the Wall Street Journal has documented the non-price rationing methods used by American hospitals. For an economist, this is not surprising: when prices don't ration demand, other mechanisms have to be brought in. But comparing the American and the Canadian health care systems shows that the solution does not lie in more state intervention but, on the contrary, in more business-like medicine.

There is not much business left in Canadian medicine. The latest issue of the Canadian Medical Association Journal reports some preliminary results from this year's Physician Resource Questionnaire, an annual survey of Canadian physicians. "Fee-for-service v. salary: the debate is heating up," runs the title.[1] Only 57% of Canadian physicians get the bulk of their incomes from fees for service, down from 68% in 1990. Most others are paid fixed salaries by some bureaucratic organization.

There is nothing wrong with different preferences and choices regarding modes of remuneration, except when some impose their preferred solution on everybody else. And this is what collective choices, by definition, do. Many, if not most, doctors and politicians now seem to think that profits and health care are inconsistent. This idea is defended by physician James P. Whalen in the latest issue of The Independent Review.[2] Dr. Whalen argues that "the business model of medicine is changing the profession of medicine," and that medicine should be viewed instead as a 'social service.' He talks about the "uncritical, frightened consumers" who were "formerly known as 'patients' when medicine was not a business."

In fact, there is no incompatibility between profits and health. Medicine is a business. To see this, however, one must think in economic terms, i.e., consider the consequences of individual choices and social institutions, which is the subject matter of economics. In the same issue of The Independent Review, Professor Robert L. Ohsfeldt, an economist who teaches health management and policy at the University of Iowa, replies to Dr. Whalen and defends free-market medicine.[3]

Why are economists and physicians so often at odds on social issues such as these? If the discussion is diseases and cures, we naturally expect the economist to lack the physician's theoretical framework of concepts and theories, and to make simplistic statements. When the debate is individual choices and health care policies, the simplistic handicap shifts to the physician, who has no clear concept of cost, benefits and choice, and cannot, qua physician, analyze the social consequences of individual actions.

If you take profits out of health care, Ohsfeldt notes, you end up with the physicians, whatever their forms of remuneration, as the only profit center. Or, at least, this was the case before the state moved heavily in this business. Now, physicians are not the only profit center, as bureaucrats and unions of support personnel will soon remind you.

Profits are inseparable from human action. Hippocratic scholar Jacques Jouanna writes, "While there is evidence that poor persons were among the clients of the Hippocratic physician, to make Hippocrates into a minister of the poor requires passing over in silence the fact that he treated wealthy clients as well."[4] Medicine has always been a business, whether for the free practioners, or later for the established practioners protected against competition by their medical corporations, or now for the medical state apparatchiks. Medicine is always a business for somebody: the only question is, For whom?

The answer does have consequences. When profits are officially suppressed and are bulged towards the apparatchiks, the incentives to satisfy consumer demand diminish. This explains the poor state of the Canadian health care system: Ohsfeldt reminds us that "the mean waiting time for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head in Canada in 1997 was [as evaluated by a 1997 study] 150 days, compared to 3 days in the United States."

The debate about the Canadian and the American health care systems often ignores other important facts. The accessibility problem of the latter is not nearly as bad as it seems: among the 30 to 40 million Americans who do not have health insurance, only about one third are chronically uninsured; the remaining two thirds are between jobs, or just out of Medicaid, and remain uninsured for a median spell of six months. And the Canadian system is not as freely accessible as it looks, for some people jump the queues, i.e., make others wait longer — sometimes too long for them to need anything any more! [5]

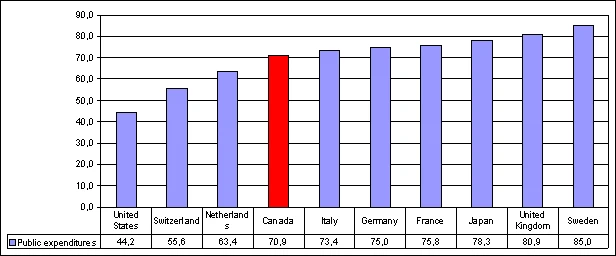

Another important fact is that the American system is far from being a private system: it is regulated at every step, and 44% of health expenditures come from the public purse. The American health care system is only not as nationalized and as bad as the Canadian system.

From the economist's viewpoint, what counts is consumer welfare. Economists don't give a damn about suppliers, except to the extent that they are prevented from satisfying consumer demand. The question is, If you were ill, would you prefer to be treated by a competent, benevolent, unionized bureaucrat who considers you part of his nine-to-five public-service mission, or by a competent entrepreneur who will get more money if you get well?

Dr. Whalen's complaint that American hospitals are wasting too many resources trying to attract customers sounds out of this world. Joan Robinson, the late Marxian economist, wrote that "the misery of being exploited by capitalists is nothing compared to the misery of not being exploited at all." We could paraphrase by saying that the misery of being subjected to advertising by private health providers is nothing compared to dealing with bureaucratic providers for whom you are a patient burden.

Public expenditures as a proportion of total expenditure on health, 2000

Source: OECD.

Footnotes

[1] Shelley Martin, "Fee-for-service v. salary: the debate is heating up," CMAJ 169-7 (September 30, 2003), at http://www.cmaj.ca/content/vol169/issue7/index.shtml#NEWS (visited October 18, 2003).

[2] James P. Whalen, "The Business Model of Medicine: Modern Health Care's Awkward Flirtation with the Marketplace," The Independent Review 8-2 (Fall 2003), pp. 259-270; soon available at http://www.independent.org/review.html.

[3] Robert L. Ohsfeldt, "If the 'Business Model' of Medicine is Sick, What's the Diagnosis and What's the Cure?", The Independent Review 8-2 (Fall 2003), pp. 271-293; soon available at http://www.independent.org/review.html.

[4] Jacques Jouanna, Hippocrates (Baltimore and London: John Hopkins University Press, 1999), p. 118.

[5] See Pierre Lemieux, "Health Care's Hidden Costs," Financial Post, August 28, 2003; reproduced at http://www.pierrelemieux.org/arthidden.html.

Other Works by Pierre Lemieux

from The Laissez Faire Electronic Times, Vol 2, No 42, October 27, 2003